The Tunuí-Cachoeira indigenous community, at Alto Rio Negro Indigenous Territory (IT), in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, municipality of Amazonas – considered the most indigenous in Brazil –, preserves its ancestor’s Baniwa ethnic group tradition. The routine involves daily activities in plantation fields and fishing, during which men and women have defined roles, and the nearly 1,300 families organize themselves around collective well-being and the preservation of indigenous knowledge and ways of life, which include daily bathing in rivers and the ceremonies performances with dances and music.

The simplicity of the daily life, however, contrasts with a challenge that impacts Brazilian indigenous populations: preservation of their languages. Artur Garcia Gonçalves, from the Baniwa ethnic group, with a doctorate from the University of Brasília (UnB) and a postdoctoral fellow at the Goeldi Museum, comments he taught classes to the community for 12 years and, despite the increase in the number of teachers who speak their native language, the difficulty in keeping it alive remains the same.

“There are 8,827 people of Baniwa ethnicity throughout Brazil and 6,338 speakers. In recent years I have seen that their numbers are decreasing, and they have stopped speaking their own language. The challenge today is the lack of teaching materials in their own language. They are only using Portuguese and English textbooks to teach, and this is worrying, considering the importance of valuing the language, since the students are all Baniwa speakers,” says the professor.

In the municipality of Seringueiras, in Rondônia, the indigenous community living in the Aperoi Village faces similar obstacles. The indigenous teacher Mário de Oliveira Neto Puruborá works at the Iwara Puruborá School. The Puruborá indigenous language – “the people who turn into jaguars,” from the Puruborá family –, belongs to the Tupi linguistic trunk. He says that the challenges of maintaining the original oral tradition arose during the European colonization period and have persisted ever since because many relatives have dispersed due to the lack of territorial demarcation.

“Our village has about twelve families with a total of 35 people, including children and adults. Because our territory is not demarcated, many do not live here. The prohibition of our traditional cultures after contact (with the colonizers) and, later, the enslavement of our people were very significant, this is why today we are facing difficulties to recover all this. Most of the elders have already passed away,” says the teacher.

Multimedia dictionaries are allies

Currently, Mário Puruborá is the only fluent speaker in the village, but he says he has been helping other indigenous people learn Puruborá. In the 1980s, the language was considered extinct, but in the beginning of the 21st century, the village reclaimed its rights, and, with the use of technological resources, they have managed to maintain the oral tradition in its original form, unlike those who live in other regions.

“Today, fluent, I'm the most skillful, but I have students who are learning well. The number (of fluent speakers) is growing. I'm very happy to see that these technologies, in part, have helped a lot,” celebrates Mário.

The technology he refers to is the Multimedia Dictionaries of Indigenous Languages, launched in April of 2025, during Indigenous Peoples Month, by the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi [Pará Museum Emilio Goeldi]. The project coordinator is the Museum's researcher and linguist Ana Vilacy Galúcio, who sought easy-to-use tools to teach young people and adults how to revitalize their mother tongue and strengthen the linguistic struggle.

“In 2019, the project started from a request of a chief named Augusto Kanoé, from the Kanoé people of Rondônia. He wanted resources he could use to learn his mother tongue, since his parents spoke it, but he spoke little and his children didn't know any word. He didn't know the pronunciation of the words and wanted to know how he could listen to it. So, it is then that, we started thinking and ended up with this production of the multimedia dictionary, in which you insert information, including writing, images, and specifically audio. And then you can listen to the spoken language,” explains Ana Vilacy.

SEVEN WORKS

The digital platform provides seven bilingual dictionaries in free, open-source, and easily accessible software covering the following indigenous languages: Kanoé-Portuguese, Oro Win-Portuguese, Puruborá-Portuguese, Sakurabiat-Portuguese, Salamãi-Portuguese, Wanyam-Portuguese, and the dictionary of Sacred Places of the Medzeniakonai People. Three other translations are already underway by the Museum's team.

Mário Puruborá, who contributed to the project, says that the digital material can strengthen a culture that has become fragile over time. "In my view as a knowledgeable teacher, I feel very concerned because I see our cultures weaker and weaker, the language ceasing to be used, parents do not speak it in their daily lives. That is why indigenous school education with teaching materials from each indigenous people is so important for the culture to remain strong and vibrant," says the indigenous educator.

We need to preserve not to die

According to the 2022 Demographic Census, from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics], Brazil has 295 spoken indigenous languages and 391 ethnic groups. The data also indicate that 1,694,836 indigenous people spread into 4,833 municipalities in the country, which represents less than 1% (0.83%) of the total 213 million Brazilian inhabitants.

Nevertheless, research from the Emílio Goeldi Museum points out that the number of languages spoken today in the Amazon is, in fact, a snapshot of those that survived centuries of exploitation, exogenous diseases, colonial violence, slavery, and dispossession. The survey considers that, before the invasion of the Europeans, there were more than a thousand indigenous languages. The process of erasing oral traditions continued until around the 1950s, period during which governments of the Amazonian countries stigmatized the native languages and oppressed the indigenous peoples, causing extinction and lack of documentation of the languages.

And many other languages are still at risk of disappearing. In fact, all of them, as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has warned through data presented in the Atlas of Endangered Languages. The concern is so great that, in 2019, the UN General Assembly proclaimed the years 2022 to 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages, a declaration that hopes not only to preserve traditional oral traditions but also to allow them to be passed on to future generations.

For researcher Ana Vilacy, the great-granddaughter of an indigenous woman kidnapped at a young age and forced to marry her kidnapper, and whose information about the ethnic group remains without any indication of concrete responses, it is essential to defend the history of traditional peoples through their oral tradition.

SPEAKERS

“There are languages that have only one, two, four speakers; groups that have perhaps ten. Few languages in Brazil have more than a thousand speakers, and perhaps only two or three have more than 10,000 speakers. Regarding what is a safe, unthreatened language, any language with fewer than a thousand speakers is a threatened language, because one thousand is a very small number. Despite the fact that the language is being learned by children and has been taught in school, this language can still disappear in a catastrophic event of any kind,” she states.

It is in this context that the Museum and the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) have maintained, since 2023, a collection of the Programa de Documentação de Línguas Ameaçadas [Endangered Languages Documentation Program]. The initiative is carried out in partnership with the communities of the Rio Guaporé Indigenous Territory, in Rondônia, to preserve the Makurap, Wayoro, and Djeoromitxí languages. Also, under the coordination of linguist Ana Vilacy Galúcio, the final material will be shared with the native population and will become part of the permanent collection of the Indigenous Languages Archive of the Emílio Goeldi Museum.

MULTILINGUAL DEMOCRARY

The 1988 Federal Constitution is a true landmark for the rights of Brazilian citizens, guaranteeing the freedom to choose representatives, both in the Legislative and Executive branches, without distinction of color, race, or gender. It also put an end to the State's tutelage over indigenous peoples, which, before its promulgation on October 5, 1988, considered native peoples unfit to elect politicians and represent themselves before the Brazilian justice system. The only thing missing was more accessible information.

In 2023, the Magna Carta was translated into Nheengatu, the only language descended from Old Tupi that is still alive. Two years later, the federal government translated the so-called Citizen Constitution into the three most widely spoken native languages in the country: Tikuna, Kaiowá, and Kaingang.

Furthermore, the state of Amazonas has currently 17 official languages, and Portuguese is just one more. This is a cause of joy, but also of perseverance for the indigenous people who live in the region, such as Professor Artur Gonçalves, whose name in Baniwa is Walipere. “I am happy to know that Amazonas has 17 co-official languages. This is an achievement of the indigenous peoples over time, but at the same time, I see that there is still a need for strengthening the language policy in the state and municipality for these languages to function in practice,” says Walipere.

The Pará Regional Electoral Court's guide promotes inclusion

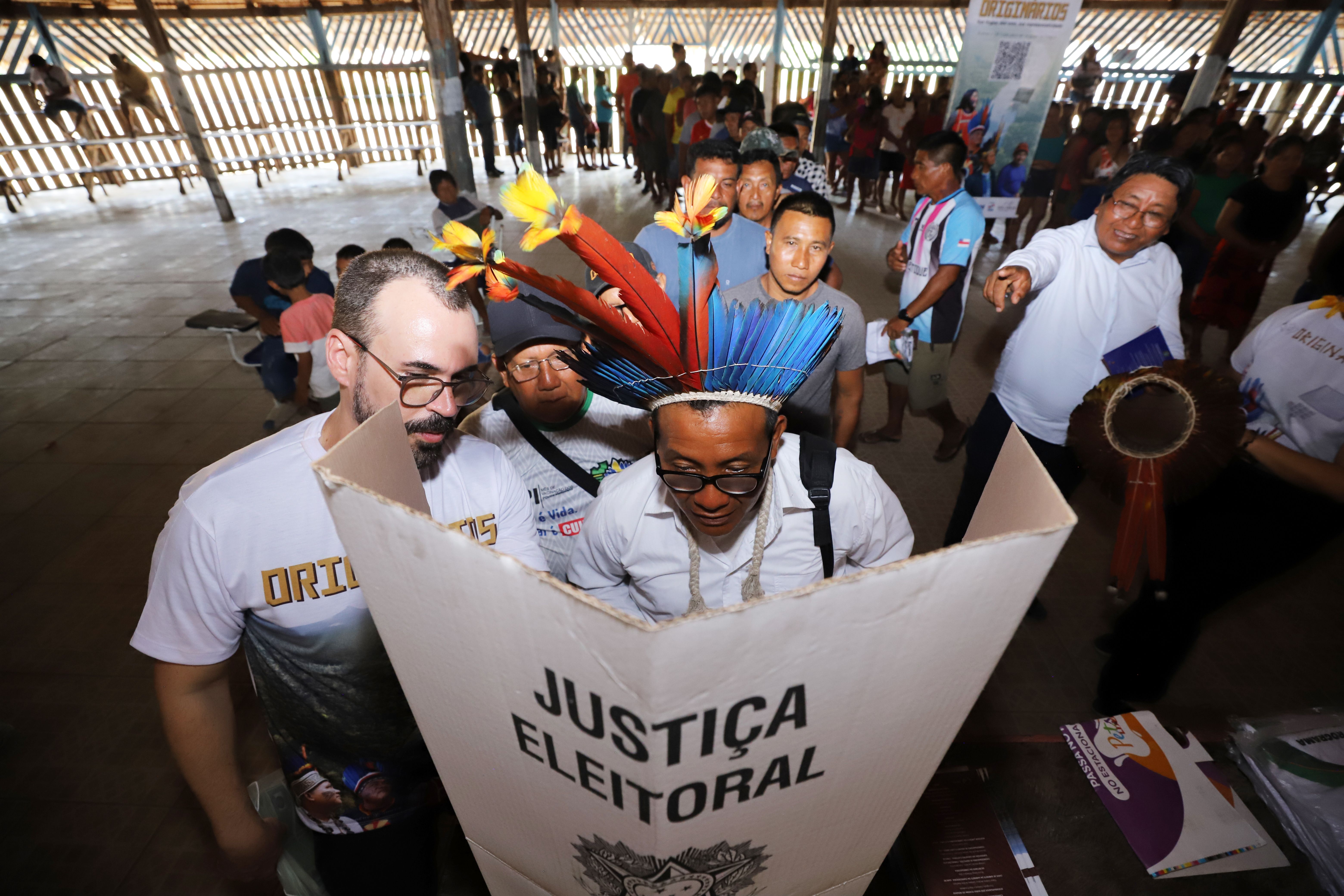

Another important instrument for accessibility and assurance of indigenous peoples’ rights is the translation of the electoral process into native languages of the Amazon. The project entitled “Guia Originários” [Guide to Originary Peoples], from the Regional Electoral Court of Pará (TRE Pará), was launched in 2024 and translated into four traditional languages: Munduruku, Tenetehara, Nheengatu, Wai-wai, and Mebêngôkre. According to the vice-president and inspector of the TRE of Pará, Judge Filomena Buarque, the initiative considers the broad sociocultural diversity and significant presence of indigenous peoples in the state.

“Throughout the institutional actions aimed at engaging with these communities, it became evident that language is a determining factor in ensuring a full understanding of the electoral process. Thus, the ‘Guia Originários’ was meant as an initiative to value Indigenous identities and promote democratic participation, providing electoral guidance in an accessible, respectful language connected to local realities,” explains the judge.

The bilingual guides provide information on how to obtain a voter registration card, make corrections to voter registration information, the security of the electronic voting machine, what can and cannot be brought to the polls on election day, as well as explanations on a sensitive topic for indigenous voters: vote buying and freedom of citizenship. This is a step that values democracy and the perpetuation of native languages.

“When an indigenous language is incorporated into an institutional initiative, it stops being just a cultural element restricted to daily community life and begins to occupy a space of social legitimacy, which strengthens identity pride and encourages its maintenance, especially among new generations,” says the magistrate.

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERSHIP

The production of Liberal Amazon is one of the initiatives of the Technical Cooperation Agreement between the Liberal Group and the Federal University of Pará. The articles involving research from UFPA are revised by professionals from the academy. The translation of the content is also provided by the agreement, through the research project ET-Multi: Translation Studies: multifaces and multisemiotics.