Netflix’s latest Brazilian production, Pssica, premiered on the platform in August to resounding global success. Set in Pará and tackling themes such as human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and urban violence, the series entered the top 10 in 68 countries where the streaming giant operates. In Brazil, it claimed the number one spot, surpassing the platform’s flagship series at the time, Wednesday.

The series Pssica is inspired by the homonymous book by Edyr Augusto, a writer from Pará. The interest in the work of an Amazonian author, who portrays the reality of the region, raises an important question: is there greater national interest and visibility for literature produced in the Amazon today?

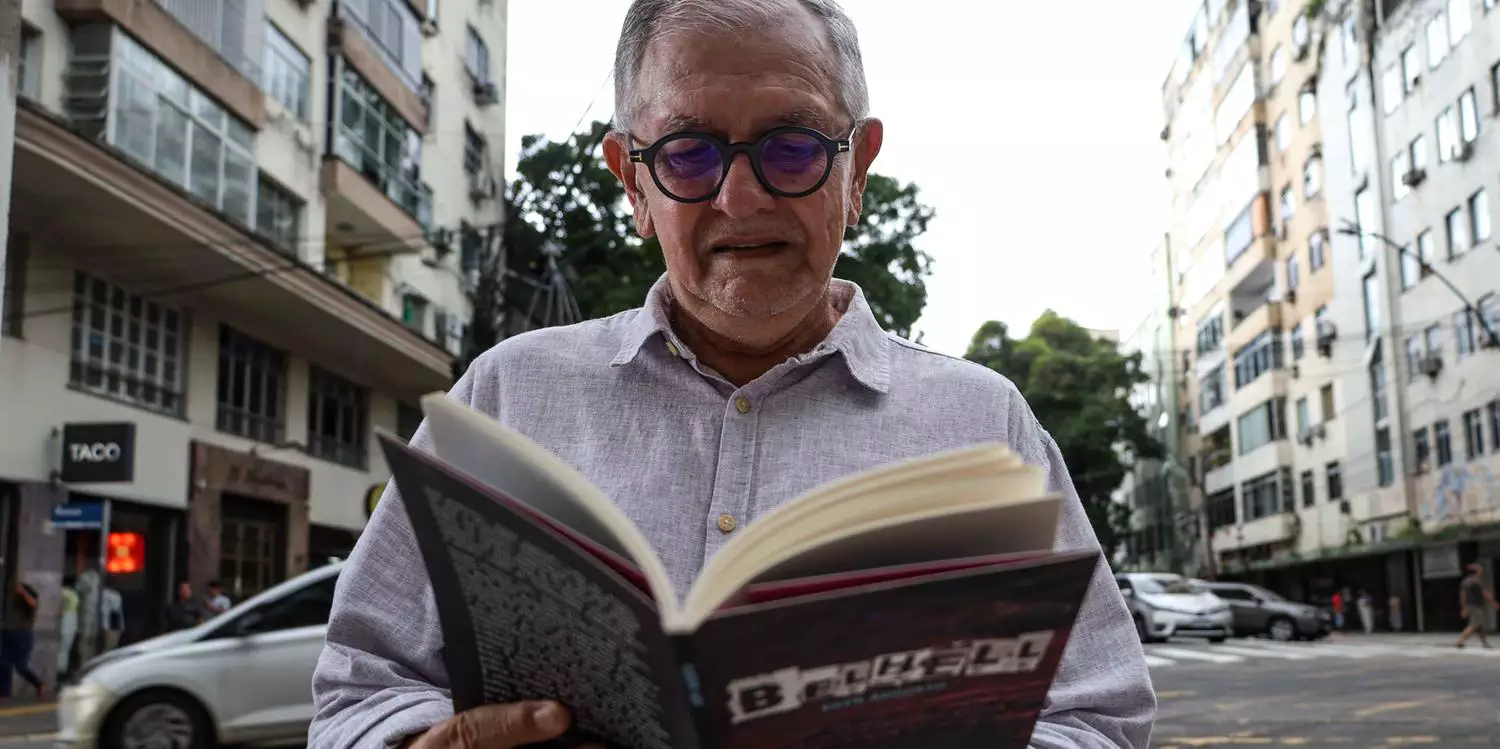

For Edyr Augusto, the series is an opportunity for Amazonian writers to “break through the bubble” of the national market and reach a wider audience. “I hope this is a chance not only for me, who have been writing for 27 years and have 19 published works, but also for other authors. May it spark curiosity about our work, about our region, because we have so much to offer, so much talent,” he says.

DEBATE

“I write about my city, Belém, my home, my land. I believe that authors who, even if not born in the Amazon, but in some way show a sense of belonging to the place can also be considered Amazonian literature,” he stresses.

Paulo Nunes, a literature professor at the University of the Amazon (Unama) in Belém, advocates for the use of the term “Amazonian expressive literature.” “It’s a way of reflecting on forms of power, our being, and our place in the world. It can be created by natives or not, but it requires a connection to our surroundings. This sense of identification doesn’t leave us adrift; it’s as if our boat seeks, in the wide river of metaphors, a harbor: Brazilian literature,” he says.

Lara Utzig, a writer, university professor, and PhD in Literary Studies from Macapá, in the Amapá state, says that the debate over the concept is longstanding and delicate, without a clear conclusion. “More than finding a single definition, I think it’s important to consider the plurality, about Amazonian literatures, because the Amazonian existence is not the same for everyone. It’s necessary to dismantle the imagination that exoticizes the region,” she points out.

LABEL

Local writers and intellectuals criticize the label of “regional literature” applied to works produced in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, while the Center-South axis is said to produce “Brazilian literature.” Lara Utzig has two published poetry collections: Efêmera and Disforia de Gênesis. The books address themes such as the inexorability of time, love, and a sense of not belonging, without necessarily including elements associated with the region.

“What motivates me to write is to tension the words amid everyday experiences. And what is expected of a Northern author is that they bring themes related to this local color. It’s an attempt to box us in, to write about the forest, about the river. These experiences influence us, and it’s inevitable that they shape our writing. But this dichotomy, the debate between regional and universal, is something constructed, and it reinforces stereotypes. It carries a pejorative connotation,” she warns.

Professor Paulo Nunes believes regionalism is a double-edged sword. “On one hand, it can help to achieve a certain recognition, as a symbolic expression distinct from the rest of Latin America. On the other, it can carry a discriminatory purpose: it’s regional because it’s exotic, folkloric. And this latter meaning does not serve our interests,” he states.

The Amazon and its elements as a setting

While authors like Edyr Augusto write specifically about the region—its reality, its charms, and at the same time its problems – there are others who use it as a backdrop to explore genres such as horror, fantasy, or science fiction.

Giu Murakami, a writer and lawyer from Pará, for example, writes fantasy and science fiction genres. Her two works, Aprendiz de Erveira and Crônicas Fantásticas de Famílias em Apuros, incorporate aspects of her Amazonian and Japanese-Brazilian heritage. “I’m interested in exploring how people relate to the future and technology. In Aprendiz de Erveira, I depict a cyberpunk future in which Belém is filled with flying cars, yet chaotic traffic on Almirante Barroso Avenue persists, alongside socio-economic conflicts that seem inversely proportional to technological advances. In the story, the main character discovers the power of herbal baths to confront villains. I also often draw on Amazonian cultural traditions as a form of cultural resistance,” Murakami explains.

The writer and journalist Iaci Gomes, conversely, embraces the horror genre, often setting it in the Amazon. Her first work, Nem Te Conto, features horror stories set in cities in Pará, with references to local cultural elements. Her second book, Visagentas, reimagines classic stories of Pará's "visagens", a local term for ghosts, but from a female perspective.

“My work deals with themes related to the region because I firmly believe it’s good to write about what you know. But people from the Amazon write about everything. A writer from here won’t always write about the Amazon, and that’s perfectly fine. I am a writer who lives in the Amazon and I write horror set in the Amazon, but I also write stories without specific local characteristics. So, I see it as national literature, and I am a Brazilian writer," she reflects.

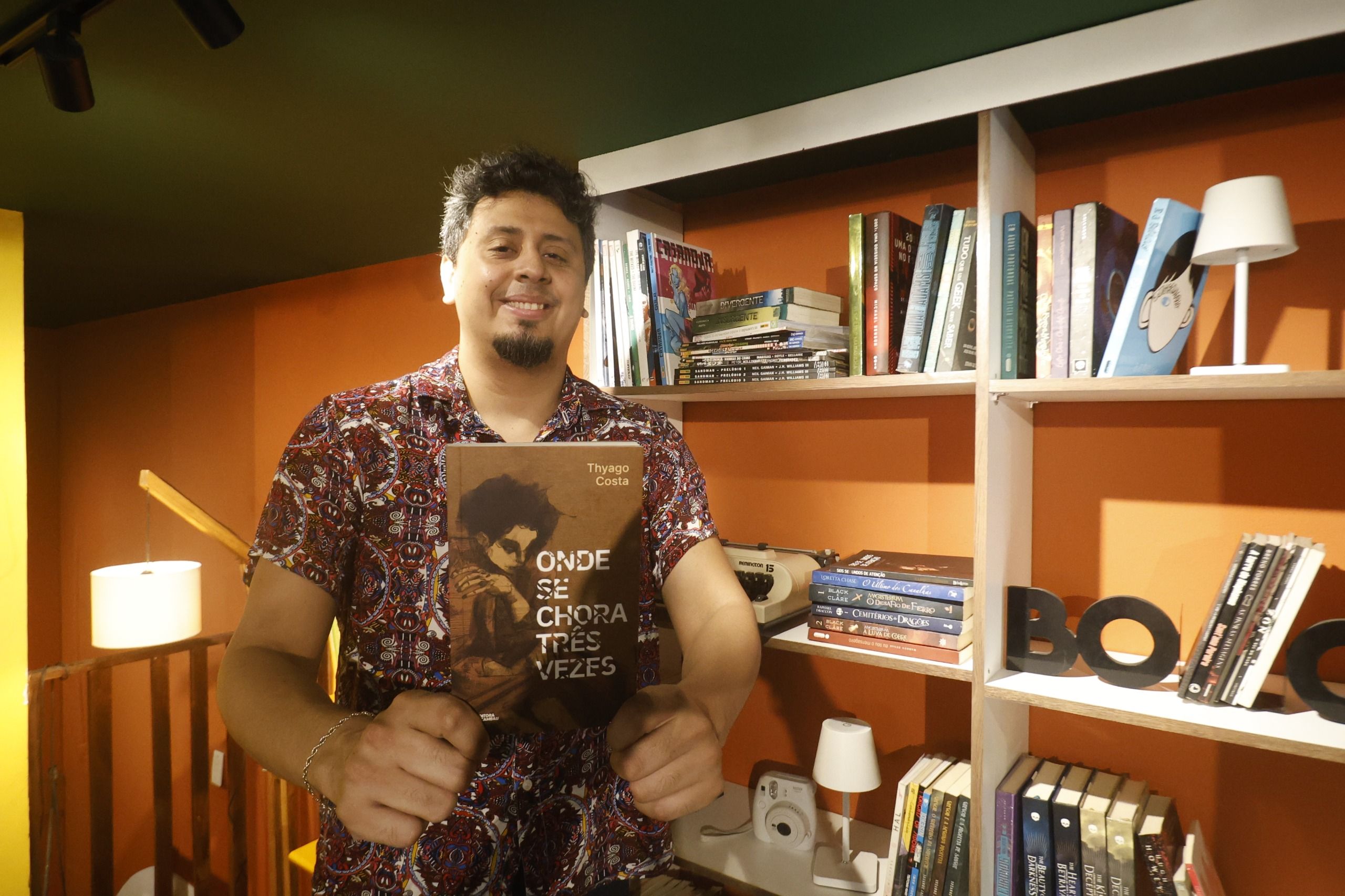

The first book released by Thyago Costa, a writer, bookseller, and graduate in Letters from Pará, also features stories set in the Amazon, more specifically in Marajó, where he was born. “Onde se Chora Três Vezes contains ten stories set in Breves, where I lived until I was 18, a town deeply ingrained in my mind and experiences. These are stories about people who live there and try, in some way, to reconcile with the town, understand their place, or even escape from it,” he explains.

From local to Universal

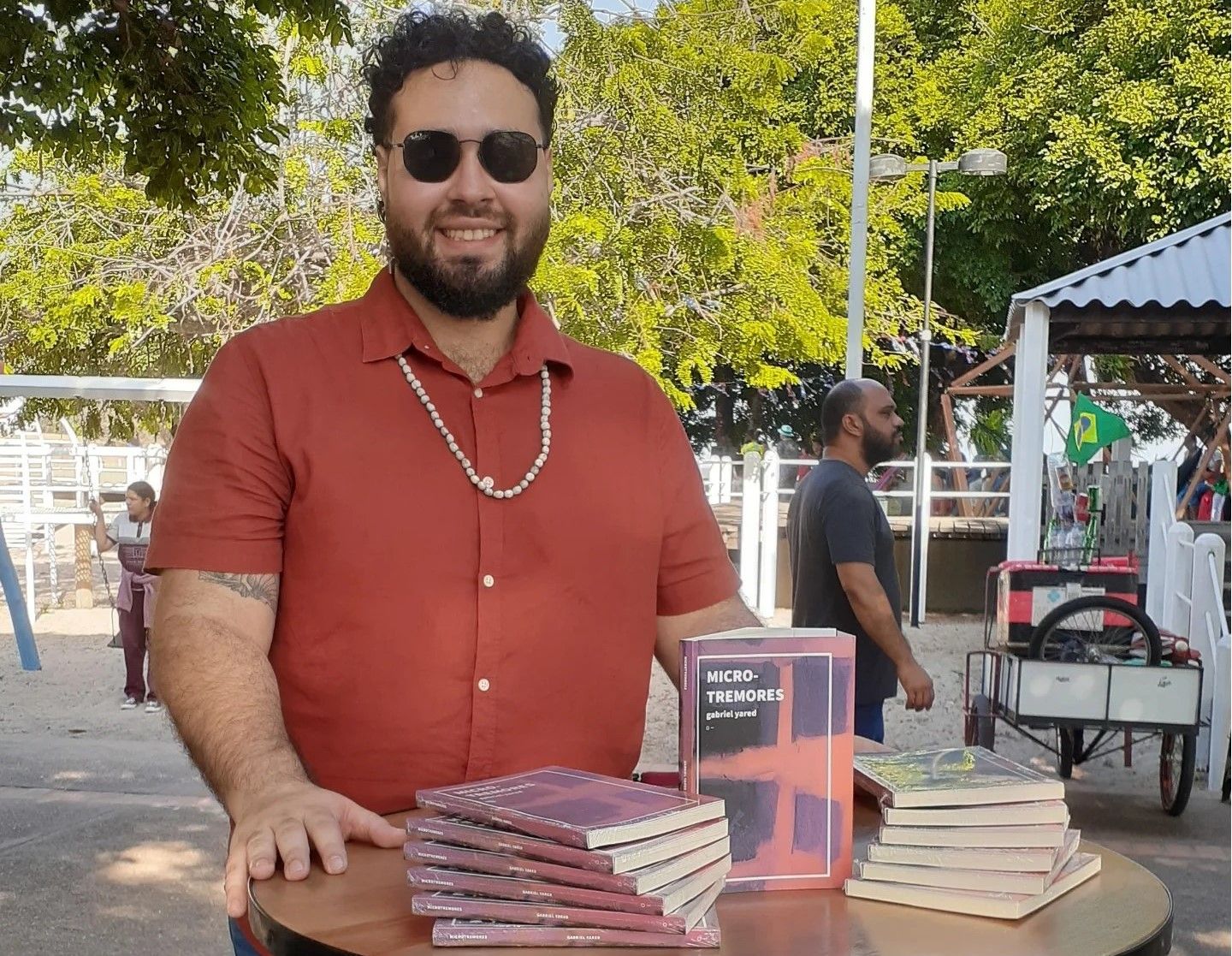

Similarly to Lara Utzig, other Amazonian authors explore universal themes while still identifying themselves as producers of Amazonian literature. The writer and teacher Gabriel Yared, from Amapá, for example, has published four books: Semente de Sangue, As flores e as dores que ele me deu, Desterra, and Microtremores. Only the first is set in a municipality of Amapá.

"My work navigates through various existential, emotional, identity-related, and social themes. I believe there are many ways to define Amazonian literatures, because it could never be just one, given that the Amazon is so vast in territory, ideas, peoples, and ways of seeing and living in the world. For me, the crossroads that marks the ‘amazonality” of a work is precisely this experience of living in the Amazon: being or residing in the Amazon is something that will inevitably show through the writing of anyone, whether born there or not," she remarks.

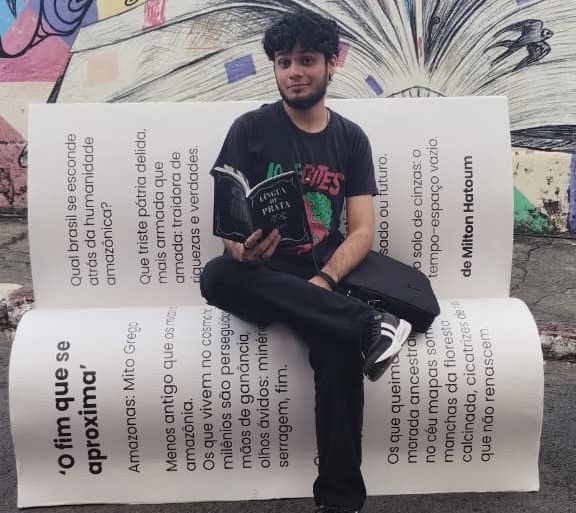

Felipe L. Cavalcante, a writer and graduate in Letters from the state of Amazonas, has embraced the genres of fantasy and horror in his writing. In addition to short stories published in anthologies, he has also released the book Língua de Prata e Outras Histórias. “I try to write speculative fiction, which is a theme that fascinates me. To me, Amazonian literature is that which is created by Amazonians. It doesn’t need to be about the meeting of the river waters, the sumaúma tree, or the forest. It can include regional settings, but should not be limited to them. We are multiple and complex, not a monolith. Our art must reflect this complexity,” he emphasizes.

Mary Abade, a writer from Tocantins with several digitally published books, explores themes like maturity, self-discovery, and youth. “Besides being from the North of Brazil, I am also a black and lesbian woman, which makes me more inclined to incorporate these experiences into each of my works. To me, Amazonian literature is that produced by Amazonian people and influenced, even minimally, by their life experiences. I don’t like to think about other requirements. This opinion is shaped by my experience of living in a state that is often considered not Northern enough – which is, in fact, the reason I prefer to write stories set in fictional towns with local influences,” she explains.

National recognition

Almost all of the authors interviewed agree that the literature produced in the region has gained greater national visibility, as exemplified by the Pssica series, the election of Milton Hatoum from Amazonas to the Brazilian Academy of Letters, or the Jabuti Prize awarded to the short story collection Flor de Gume by Monique Malcher from Pará, who has just released her new work, Degola, through a major national publisher.

Giu Murakami believes that social media have helped people get closer to the publishing market. “I think publishers have been increasingly investing in Amazonian narratives, not only due to international interest but also because of society’s own interest in stories set in the region,” she suggests.

The writer and master’s degree holder in Literary Studies from Amazonas, Jan Santos, offers a more critical perspective. “Visibility is a strange thing. Everyone knows we exist, everyone knows we produce, but there is no real interest or openness to our contributions. The Amazons have been in the spotlight because of events like COP 30 (the United Nations Conference on Climate Change, 2025) and the interest they generate, but that’s all. Even COP itself is shaped from an outsider’s perspective, offering few opportunities to those who truly know these territories,” he reflects.

CHALLENGES

For Edyr Augusto, it is still very difficult to “break through the bubble” and reach stronger publishing markets, such as those in the Southeast. “It used to be very bad; now it’s less bad. But many people still have to move there to be more visible,” he says.

According to Giu Murakami, the main obstacle is structural and logistical. “Participating in national literary events requires a significant financial investment, which makes it difficult to build networking within the publishing industry,” she explains. However, the author notes that there is a strong sense of community among Amazonians, whether through the formation of collectives, the joint publication of digital literary magazines such as Égua Literária, which she and Gabriel Yared contributed to, or the growing number of small publishers emerging in the region.

Thyago Costa believes in the power of collective organization. “It’s very difficult to ‘break through the bubble’ alone if you don’t join groups and move beyond an individual approach to promote your work,” he states. Felipe L. Cavalcante shares the same view. “Authors need to come together and seek visibility through collectives, with one author supporting and recommending another,” he suggests.

Moreover, the role of public institutions is seen as fundamental. The magazine Égua Literária, for example, was created with funding from the Aldir Blanc Law. “Public support is essential for us to continue revitalizing the local literary scene. We have powerful voices that can greatly enrich contemporary literature. If we publish, diversify, use digital technologies to our advantage, and seek ways to be exceptional, what more is needed for us to be heard?” Jan Santos asks.

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERSHIP

The production of Liberal Amazon is one of the initiatives of the Technical Cooperation Agreement between the Liberal Group and the Federal University of Pará. The articles involving research from UFPA are revised by professionals from the academy. The translation of the content is also provided by the agreement, through the research project ET-Multi: Translation Studies: multifaces and multisemiotics.